Nick Merriman has been CEO of the Horniman Museum and Gardens since May 2018 and was previously Director of the Manchester Museum for 12 years. During this time, he focused its mission on contemporary issues, doubling visitor numbers to over 500,000 a year.

At the Museum of London, in his first role as Curator of Prehistory and subsequently Head of Early London History and Collections, he led a pioneering project, ‘The Peopling of London.’ This explored London’s cultural diversity from ancient times to the present.

From 2004-06, he was in the first cohort of Fellows on the Clore Leadership Programme, while Director of Museums and Collections, and Reader in Museum Studies at University College London.

An interest in archaeology

Nick Merriman studied archaeology at Cambridge, but his background was not academic. He explains his route into the sector:

“ Both my parents left school at 16, so they didn’t have an extensive education. I had a free place at a very good secondary school in Birmingham, where I benefitted from a wider range of influences. My dad was keen for me to be a solicitor, but he also enjoyed going around junk shops in Birmingham, finding old things.”

“I followed him around, got interested in collecting bottles, and then got a metal detector. And through that, I discovered archaeology.

“From the age of 16, I’d spend weekends going on an archaeological dig near me. I decided to go to university, not to study law, but to study archaeology. It was really only because a primary school teacher said, ‘this boy should do the King Edward School entrance exam’ that those aspirations could go further.”

Museums and accessibility

After studying archaeology, Nick Merriman had to decide what to do next:

“I could have become an archaeologist,” he says. “Unfortunately, I was foolish enough not to focus on the Mediterranean, but on Northern Europe. I realised I’d be spending my winters on my knees in mud.”

He had always had a particular interest in archaeology’s purpose. So, museums presented an interesting option:

“I applied to go on a museum studies course at Leicester. I did that for a year and then went back to do a PhD. The other strand running through this is that because my parents, who are perfectly intelligent, left school quite early. I always thought they’d been denied the opportunity because of the circumstances they were born into. So the major strand running through my entire career has been trying to promote access.

“My PhD was on why do certain sections of the population not visit museums? Why are museums not more accessible ?”

Exploring barriers to entry

Merriman did a survey of a representative sample of the entire population of Great Britain, looking at their attitudes to museums, heritage attractions and the past:

“What that showed was that everybody is interested in the past, but only a section of the population expressed interest through visiting museums. It isn’t through lack of interest. People self-exclude because, ultimately, they think museums are not for them.”

“The barriers are not physical or even necessarily financial, but attitudinal. Many people don’t even go to free museums. I wanted to understand what those barriers were, and have tried to spend my career dismantling them.”

Towards the end of his PHD, he saw a job advertised at the Museum of London.

“I had visited it in the year it first opened when I was at school, and thought, ’This is a fantastic museum. What a great place that would be to work.’ When I saw a job came up as Curator of Prehistory, I had studied prehistoric archaeology, and I thought I should apply.”

Much to his surprise, he got the job.

“I wasn’t expecting it,” he says. “I continued my PhD grindingly slowly, part-time, and eventually finished it a few years later. And I started my job as Curator of Prehistory. There was no such thing as management then; my boss said, ‘There’s your desk; just find your feet. We haven’t got a plan for you.’”

Nick Merriman and the Museum of London

He set about getting to know the collections.

“But the preamble to that draws the strands together, when after a few years I was looking at a way of making prehistoric times relevant to today. A lot of people think of prehistory as boring. There are misconceptions about dinosaurs and old flints and bits of pottery.

“But I realized that there was a point during the last ice age, about 15,000 years ago, when there were no people in Britain, which was a peninsular of Northern Europe, and the sea levels were lower because of the ice sheets.”

“Then, when the ice sheets started melting, plants and animals started colonizing Southern Britain. And people started following, going across the land bridge where the Channel is now. So there was a point at which we were all immigrants”

This, he explains, was in the early 1990s, when the British National Party were beginning to make inroads politically in London for the first time, winning council seats:

“I had a very purist view. Part of their narrative was that Britain had been a pure white nation until the second world war when all these immigrants came over.”

The history of London

Pond Dipping at the Horniman. Photo by Megan Taylor

Nick Merriman felt this should be challenged. It was simply wrong, not as a political point, but as an academic point about accuracy:

“As I say, if you go right back, we’re all immigrants. And, of course, London was founded by immigrants: the Romans. Then there were the Anglo-Saxons and Normans; there were the Flemish weavers, the medieval Jews who were expelled in 1290, the Huguenots, et cetera.

“I realised that there was another history of London that needed to be told, from the point of view not that immigration is a recent problem, but that immigration is fundamentally the reason why London has persisted as a world city for 2000 years. It’s because of immigration that London is great, not despite it.

“With a kind of light bulb moment, I realised I could make prehistoric times relevant and link to contemporary debates.

“I put forward a proposal to the museum’s Exhibitions Committee that we do something called ‘The Peopling of London: overseas settlement from prehistoric times to the present’, or something like that. And they agreed.”

Leading a pioneering project

He moved temporarily, in 1993, from his role as Curator of Prehistory to being Head of Early London History and Collections, leading the pioneering project:

“It involved pretty well everybody in the museum, searching out objects that help tell the story of immigration. We had a surprisingly large amount. In time, it wasn’t just an exhibition, but it became a book and a programme of events and activities.”

“Part of the issue then was that as the Museum of London had been configured, its historical narrative stopped at the Second World War. There was a very thin post-war section; something that was supposed to change but never did.

“People who were more recent migrants couldn’t see their story told anywhere in the museum, and so, not surprisingly, they didn’t tend to come. The idea was that, through representing that story, audiences would be widened.”

Widening the audience

Walrus at the Horniman

The exhibition was very successful. It was, at least at that point, the most popular exhibition the Museum of London had ever done.

Merriman says: “It did widen the audiences, and that breadth continued for a few years. Subsequently, the Museum of London has changed a lot. And it will be changing even further and putting issues like representation and diversity at the heart of what they do. It is one of the things I’m still most proud of.”

“Interestingly, somebody did a PhD recently in which ‘The Peopling of London’ was a major case study. I was interviewed as a historical curiosity. Curators from the Museum of London are also interviewing me to help them think about how they might plan the new Museum of London in Smithfield.”

Nick Merriman and the Horniman

Nick Merriman has been at the Horniman for two years:

“I came in after Dame Janet Vitmayer , who had been there for about 30 years and had done a fantastic job. But as with anybody coming after someone who has been there a long time, there are things that fresh eyes can bring.

“When I started, I asked, “What is the purpose of the Horniman? What are we there for?’” Most people, whether they were external visitors or staff, couldn’t identify what was important or distinctive about it.

“We did a lot of work. I did some all-staff sessions over a couple of days, with films and stimulus materials. And we realised – it was blindingly obvious, but it hadn’t ever been articulated. The Horniman is the only museum in London where you can see nature and culture side-by-side at a global level. That made it unique.”

Pollinator Bed, Horniman Gardens. Photo by Polly Heffer

The global issues now, of course, are around the environment; climate, ecology, and pollution, and issues such as migration.

“Environmental and social justice are interlinked because it’s the global South populations that are impacted by climate change. This emerging narrative came out of also looking at our audiences, which are around 70% families, mostly local and repeat visitors.

“And we know that the parents and grandparents and carers who are bringing very little children are worried about the future that these preschool kids will inherit when they reach their fifties. We know that there’s a real appetite for engagement in the big global issues.”

Changing the Horniman’s mission

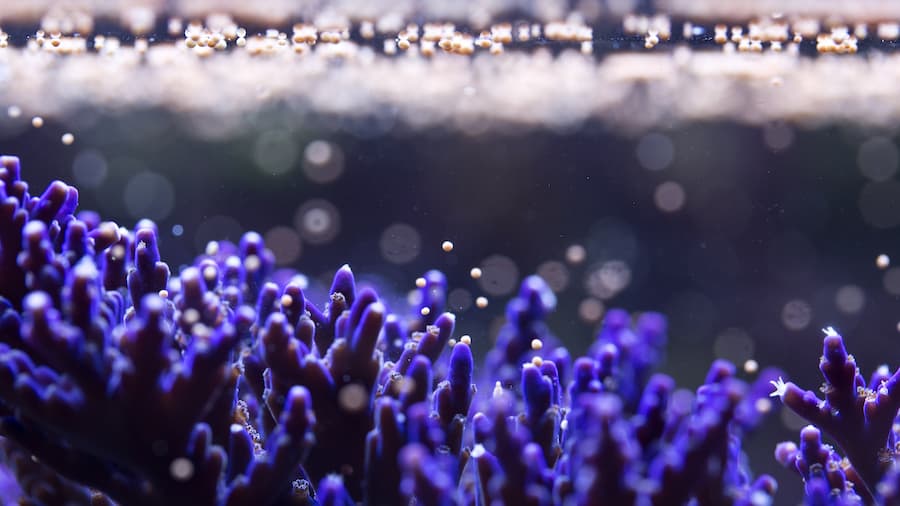

Project Coral, Horniman Museum

“We changed the museum’s mission,” says Nick Merriman. “Previously, it was about promoting an appreciation of the natural world and human cultures. It dated back to the 1980s. But we felt it was a bit weak in terms of what we’re facing now. It is now about working with our audiences to develop a positive future for the world we all share.

“ Frederick Horniman , our founder, was a Quaker and a philanthropist, who wanted to bring the world to Forest Hill. We have adopted that background as a kind of ethical signpost for us. Quakers are about brotherly and sisterly love and common humanity.

“We have gone back to that founding essence, as well as focusing on intercultural understanding and care of the environment. It means that we have a very forward-looking agenda around dealing with some global issues.”

Responding to contemporary issues

In terms of the role of museums like the Horniman when it comes to reflecting racism and colonialism, and responding to a situation like the Black Lives Matter expression of global outrage, Merriman says:

“What has come out through Black Lives Matter is entirely positive and long, long needed. As I said, I did my PhD in what was, then, an emergent museum studies field, quite a long time ago. Even then, back when I was doing critical archaeology, it was about hidden histories, transparency and equity around access and representation.

“I have been very frustrated that despite my best efforts, the sector hasn’t moved as much as I would have wished.”

Horniman Gardens Bandstand. Photo by Ludo des Cognets

The Horniman was particularly concerned about responding to Black Lives Matter. It was named on the ‘Topple the Racists’ website.

“It was one person’s nomination. Our founder was listed as ‘a tea magnate, plantation owner and collector… Arch colonialist, exploiter of empire and shameful collector of native human artefacts.’

“We had always had a rather benign view of Frederick Horniman, sort of adopting him as an ancestor that we wished for. But this did cause us to look deeper. We put something out on our website almost immediately, explaining that family money was from the tea trade, which was exploitative of people in the empire, et cetera.”

The Horniman family history

“We then did a bit more work and found that the Hornimans were wholesale merchants who bought their tea on the London market, so they didn’t have plantations,” says Nick Merriman.

The tea in question was mostly from China, it transpired:

“The East India company merchants buying tea from China were paying for it with opium grown in India. This is the reason for the Opium Wars; to force the Chinese into permitting the sale of opium. The Chinese wanted to stop it; it was an illegal trade, causing all sorts of misery.”

Horniman Natural History Gallery. Photo by Sophia Spring

A panel in the gallery now tells the story of the Horniman family wealth:

“It is called ‘Tea and Empire.’ In it, we are very explicit about the opium trade. And their blindness to that down-the-line exploitation and misery that led to the profits that they made from selling tea.”

The picture is on Merriman’sTwitter feed, with the hashtags #decolonisemuseums and #MuseumsAreNotNeutral.

“Black Lives Matter is, I feel, an entirely positive call for accelerated action from the museums and heritage sector. One that is long overdue. Perhaps we needed that external sharp push; it’s a shame we hadn’t done it of our own accord. But I’m pleased to see that it’s now strongly on the agenda.

“I want to maintain this impetus. What I don’t want is everybody to slump back to normal operations, as museums and heritage attractions get back to whatever normality pertains.”

The Horniman and COVID-19

Nick Merriman planting a tree at the Horniman Museum and Gardens

On the COVID-19 pandemic, and the environmental crisis from which it grew, Merriman says:

“We have drafted a reset action plan for the Horniman. It essentially says that COVID means that we must reset what we do. My thoughts here – this applies to the whole sector – is that the constant growth model that has underpinned the heritage and attractions business is over.

“Obviously, that is very challenging, both for the commercial attractions and for the ones with public funding, since even those with public funding, such as the big national museums, are still raising 70% of their funding from other sources.

“The operating model has been, each year, ‘We must target greater visitor numbers and greater income. And to make that happen, we must put in more capital build, more attractions.’ It is unsustainable; it always was. COVID has brought us up short to realise that. We must have a new, sustainable model.”

A new sustainable model

“For me at the Horniman, and I hope for many of my colleagues, the new model should be about diversity of audiences rather than the growth of audiences. It should be about sustainable income generation and the focus on quality of experience.

“How that works out economically is difficult to predict. There’s no doubt that we’re all having to adjust downwards to shrink our organisations to become sustainable. That has wider impacts on society in terms of people’s jobs. But the implications of dealing with COVID-19 and moving to a sustainable model is a shrinkage of the sector.”

Horniman Aquarium, Project Coral. Photo by Jamie Craggs

Individual institutions may be exceptions to this, Nick Merriman says:

“Those with large grounds, et cetera, may be able to do it in different ways. But the expectation that each year will be bigger and better than the previous one has got to change.

“We haven’t paid enough attention, first of all, to diversity. There are systematic exclusions of large sections of the population. Not just based on ethnicity but also based on class, which we don’t tend to talk about.

“At the Horniman, we haven’t done well enough on diversity of audience. We are already heading down that path, and now it’s even more important. Trying to diversify your audiences at a time of contraction is very difficult. But it is, essentially, the challenge we are setting ourselves.”